May 2017 Newsletter

Appellate Practice and Procedure: Tips and Traps to Be Aware Of in Today’s Appellate Environment

By Beth Brooks Scherer

Any licensed attorney can pursue an appeal in North Carolina’s appellate courts. In an increasingly specialized world, however, more attorneys are associating appellate counsel. Since its inception in 2011, North Carolina’s Appellate Practice Specialty has grown to include 31 board certified specialists, most of whom have impressive credentials: current and former appellate judges, solicitors general, leaders in the appellate bar, and professors of law. Those credentials are reinforced by a wealth of experience with appeals.

Any licensed attorney can pursue an appeal in North Carolina’s appellate courts. In an increasingly specialized world, however, more attorneys are associating appellate counsel. Since its inception in 2011, North Carolina’s Appellate Practice Specialty has grown to include 31 board certified specialists, most of whom have impressive credentials: current and former appellate judges, solicitors general, leaders in the appellate bar, and professors of law. Those credentials are reinforced by a wealth of experience with appeals.

One of the most rewarding components of being an appellate practice specialist is helping other attorneys navigate the minefields of appellate practice and procedure. Below are just a few of the hazards that an experienced appellate practitioner can help trial counsel navigate.

1. Avoid fatal mistakes with the notice of appeal and appellate jurisdiction.

Although filed in the trial court, the notice of appeal is the most important document in any appeal. A mistake involving the notice of appeal will usually foreclose the right to appellate review.

Because appellate practice and procedure in this area is rapidly changing, the chance of making a mistake with the notice of appeal has never been greater. During the past 18 months, the General Assembly has made numerous changes to the statutes governing the appellate jurisdiction of our state courts. Due to these changes, determining whether to appeal to the Supreme Court or court of appeals can be challenging. (If you doubt this statement, see here, here, here, and here—to name a few.) The General Assembly also recently authorized en banc jurisdiction for the North Carolina Court of Appeals and broadened the criteria for bypassing the court of appeals to obtain direct review in the Supreme Court.

In the midst of these jurisdictional changes, the appellate courts have issued numerous (and sometimes seemingly conflicting) opinions on when post-trial motions will toll a party’s deadline for filing a notice of appeal. Examples include Rule 59 motions, motions for attorneys’ fees, and another party’s post-trial motion.

Two service-related issues can also implicate your notice of appeal deadline. Moreover, the form and content of the notice of appeal are emerging trouble spots, with incomplete and premature notices of appeal leading to the dismissal of several appeals.

Interlocutory appeals in state court have always been a bit of an enigma. As a starting point, the Appellate Rules Committee’s Guide to Appealability is a great resource. The Guide, however, warns that the law of appealability “is constantly evolving” and, therefore, keeping up with case law is important. For example, if you wait until after the trial court issues its interlocutory order to ask for a Rule 54(b) appeal certificate, it will likely be too late. While no statute specifically authorizes interlocutory review of undecided, but controlling, issues of state law, an alternative method of seeking appellate review may exist—particularly for orders from the North Carolina Business Court. Also, knowing when you may, might, or must appeal an interlocutory order is critical.

Appeals involving the state as a party are not immune from uncertainty. For example, a statutory right to certiorari review exists for some types of criminal issues, but because of a gap in the Appellate Rules, obtaining review of these issues can be difficult. Oral notices of appeal are usually sufficient in criminal cases—except when they are not. And while the denial of a sovereign immunity defense has long been considered immediately appealable, a recent focus on the form of the motion to dismiss has created uncertainty in this area as well.

Finally, appeals from the North Carolina Business Court present unique—and often unseen—dangers. Seven potential snares are detailed in an article on business court appeals found here.

In short, keeping up with the jurisdictional changes and notice of appeal snares can be overwhelming—even for seasoned litigators. Consulting with an appellate practice specialist about a potential appeal is often good risk management strategy. An appellate practice specialist can help both appellants and appellees identify notice of appeal and jurisdictional errors that can torpedo an appeal before it gets off the ground.

2. An appeal is not an invitation to recycle a trial court brief.

“Our trial court brief is pretty good. We can just add a new caption, change a few words, and file it in the court of appeals.” Such thoughts are common among attorneys who do not practice regularly in the appellate courts. However, good appellate briefs usually look very different from trial court briefs. Here are a few reasons why.

A trial court’s decision is often influenced by the arguments made by counsel at a hearing, with the briefs receiving less attention. The opposite should be expected in the appellate courts. Only a small percentage of appeals receive oral argument. Instead, most appeals are decided on the briefs alone. Even if your case is selected for oral argument, your opportunity to tell a story during your 20 to 30 minutes of oral argument time will be limited by the questions being asked from the bench. Your best (and possibly only) opportunity to tell your client’s compelling story will be your appellate brief.

Appellate briefs also receive significantly more scrutiny than trial court briefs. Appellate briefs are reviewed—often repeatedly—by multiple appellate judges and their law clerks. Appellate briefs are expected to contain detailed citations to both the appellate record and legal authority. A good rule of thumb is that every sentence should be followed by either an appellate record citation and/or a legal citation. Those citations will likely be verified, with the law clerks conducting their own independent research into the law and the record. Misstatements of the law or record, erroneous citations, missing or overlooked legal authority, or defects in counsel’s reasoning are unlikely to escape this more rigorous appellate scrutiny.

Trial court authorities (i.e., federal district court and business court opinions) are not binding on the appellate courts. Nor are opinions of the court of appeals binding on the Supreme Court. A good appellate brief is mindful of this “change in venue,” updating and refining legal authority and arguments accordingly. Moreover, because both the Fourth Circuit and North Carolina Court of Appeals have en banc authority, litigants should look for opportunities to ask the full court to review decisions of prior panels, including resolving conflicts between prior panel opinions.

While often determinative of the issues on appeal, treating standards of review in a cursory manner (or omitting the standard of review from an appellate brief altogether) is a mistake. Knowing how to effectively navigate appellate standards of review is critical legal strategy.

Finally, appellate briefs should address—or at least be cognizant of—broader jurisprudential principles. Trial courts focus primarily on the cases before them. Appellate judges must be equally cognizant of setting workable precedent for the entire state or circuit. That includes avoiding taking positions on legal theories that do not need to be addressed in the current appeal, but can be saved for resolution in a future case.

Appellate lawyers frequently exercise the brief-writing skills discussed above. Some attorneys mistakenly believe that an appellate lawyer will second-guess every decision made by trial counsel. Appellate attorneys recognize the difficult job that trial counsel has. They understand that trial counsel has had to make numerous strategic decisions in an effort to win in the trial court. Moreover, an appellate attorney’s success is tied to making trial counsel’s arguments and strategic decisions in the lower court look good—not tearing them down. For these reasons, a good appellate lawyer will work with trial counsel to transform a good trial court brief into a great appellate brief.

3. Conduct your appeals with style.

While style and formatting issues are unlikely to result in the dismissal of an appeal, presentation can be important in the appellate courts. One of my favorite illustrations of this point comes from Judge Dietz, a judge on the North Carolina Court of Appeals and a board certified appellate practice specialist:

[I]t’s not just the judges who read the briefs. Judges have law clerks. Most law clerks are top-of-the-class recent law school graduates who served on the law review, [where they spent most of their time] [f]ixing cites in proposed articles to conform to the Bluebook. So when law clerks read your brief and see lots of Bluebook mistakes, they might think, “I don’t know who this lawyer is, but I know they weren’t on law review.”

Judge Richard Dietz, NCBA Appellate Practice Section CLE: I Never Thought of That! (October 2, 2015). While directed to citation formats, Judge Dietz’s statement illustrates a larger point: The style and formatting of appellate records and briefs are early signals of an attorney’s proficiency and experience in the field. Even if your style and formatting errors are not bad enough to warrant an appellate “bench slap,” they can erode your credibility.

The Appellate Rules Committee’s Style Manual is an excellent primer for appellate style and formatting practices. However, due to its length (over 100 pages) and its frequent updates (a new version is forthcoming), an appellate practice specialist can save you from having to review and digest all of its intricacies.

One way to signal unfamiliarity with the North Carolina Rules of Appellate Procedure is to submit an appellate brief in Courier font. As of January 2017, the Supreme Court has banned Courier and other non-proportional fonts from appellate briefs and records. Practitioners must instead use proportional fonts with serifs (examples include Constantia, Century Schoolbook, and Times New Roman). The page-count limitation for briefs filed in the court of appeals has also been completely replaced by a word-count limitation.

Preparation of the appellate record is another area in which style and form matter. A party’s failure to include key documents in the appellate record can result in dismissal of an appeal or automatic affirmance of the trial court’s order. (A few examples can be found here, here, and here). Does your appeal involve an exhibit that the appellate court needs to review in color to understand your case? Placing that document in the printed record will transform that color exhibit into a black and white blob. Because not all of the style and formatting procedures are found in the Appellate Rules, this is an area where experience is invaluable.

4. Find an appellate practice specialist.

An appellate practice specialist can help put the shine on your appeal. Fortunately, being a member of a firm with an appellate practice group is not a prerequisite to taking advantage of a specialist’s expertise. Appellate attorneys regularly consult with trial counsel. The State Bar’s list of board certified specialists makes it easy to find an experienced appellate attorney. Consider contacting a specialist the next time an appeal arises.

Beth Brooks Scherer is an attorney with Smith Moore Leatherwood LLP in Raleigh whose practice focuses exclusively on appeals. She has been certified by the North Carolina State Bar as an appellate practice specialist since 2011. She served as both vice-chair and chair of the North Carolina State Bar’s Appellate Practice Specialty Committee from 2011 to 2017. Beth is also a former chair of the North Carolina Bar Association’s Appellate Rules Committee. Many of the links found in this article are to posts found on Smith Moore Leatherwood’s North Carolina Appellate Practice Blog (www.ncapb.com), to which Ms. Scherer is a regular contributor. The blog focuses on practicing law before and emerging issues in North Carolina’s state and federal appellate courts.

Spotlight: Matthew W. Sawchak—Five Questions for the New Solicitor General

This month we’re spotlighting the North Carolina Solicitor General Mathew Sawchak. Sawchak served on the initial Appellate Practice Specialty Committee and was certified in 2011. He was appointed solicitor general on January 18, 2017. We asked him five questions:

This month we’re spotlighting the North Carolina Solicitor General Mathew Sawchak. Sawchak served on the initial Appellate Practice Specialty Committee and was certified in 2011. He was appointed solicitor general on January 18, 2017. We asked him five questions:

1. What does being the North Carolina solicitor general entail?

I oversee our state government’s civil appeals. I personally handle selected appeals, especially appeals to the US Supreme Court. My deputies and I also help our colleagues in the North Carolina Department of Justice with appeals. I’m honored to work with Attorney General Josh Stein.

2. What aspect of your extensive appeals experience is most helpful in your new role?

To be successful, an appellate lawyer needs to crystallize ideas and express them in a compelling way. As a partner at Ellis & Winters, I honed these skills by working with master advocates, including Dick Ellis, Don Cowan, Paul Sun, Jon Sasser, and Leslie Packer. I also handled a lot of appeals that involved the scope of government authority. I apply this training and experience in my new role.

3. What were the Appellate Practice Specialty Committee’s goals in creating the appellate specialty six years ago? Have they been reached?

When Justice Bob Edmunds led the creation of this specialty, he wanted to encourage all of us to reach for new skills—and, more importantly, to raise our level of service to the state and federal appellate courts. The specialty is achieving these goals. We are encouraging more and more lawyers to study the doctrine and the skills that an appellate lawyer needs to master.

4. How has the practice of appellate law changed in recent years?

I’d highlight two points. First, oral argument of appeals is becoming the exception, not the rule. Second, partly because brief writing has increased in relative importance, expectations for the quality of legal writing have risen. More and more thought leaders—including Chief Justice John Roberts, Professor Bryan Garner, and Judge Rich Dietz—are showing lawyers what a lean, muscular writing style looks like. In my experience, this approach to legal writing is still rare, but it produces much better results.

5. Tell us about yourself.

I graduated from Harvard College and Duke Law School. I’ve been married for almost 33 years to Maureen Sawchak, whom I met when both of us were working at—wait for it—Burger King. Our son Ben graduated from UNC and works for an e-commerce company in New York City. Our daughter Julia is a rising junior at Wake Forest. My favorite avocation is singing. I sing with the North Carolina Opera and the North Carolina Master Chorale. I’ve also done quite a bit of a cappella singing. It’s a great avocation because I can’t sing and think about appeals at the same time.

Specialization Notes: Now Seeking Applications

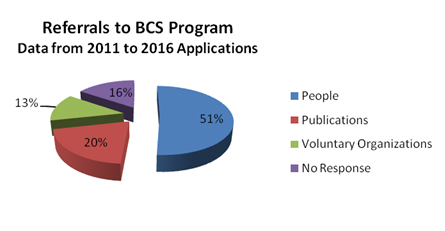

We are now accepting applications for board certification in 2017. The data shows that our board certified specialist community is our best source of referrals. As a member of that community, please help us to identify potential new applicants for specialty certification.

If you have identified potential candidates in any specialty practice area, please encourage them to learn more about our program by visiting us on the web.

- Data complied from 2011 - 2016 applications

- People: BCS attorney, partner in law firm, judge, or another peer.

- Publications: Paid advertising such as Lawyers Weekly or State Bar publication such as Specialization Directory and Newsletter, State Bar Journal ad, or article.

- Organizations: Voluntary bar, national certifier, local bars, or listserv.